THE RUSSIAN SPRING OF DONALD TRUMP

If not a traitorous Russian agent, then surely a Putin Asset

By Frank Van Riper

Photography Columnist

It says something that, after he’s been elected president twice, you can go online today and order any number of baseball caps and t-shirts asking “Is He Dead Yet?”

Though sold as “humorous” merchandise, this is only a small sign of how badly The Orange Pustule has fucked things up in the less-then-three months since he took office (again.)

The incipient dementia that he showed four years ago is getting worse (I’m talking Donald Trump, not Biden.) But, of course, that’s not all.

The economy is tanking, we have started a destructive international trade war for no good reason but his own pique, our European allies no longer trust us, Ukraine is being left to be gobbled up by a Russian thug and autocrat, while our military strategy is all but being tweeted and YouTubed by an incompetent ex-drunk (supposedly) and serial abuser.

Meanwhile the very core of the federal government is being hollowed out by a throng of unelected crypto-Nazis whose hare-brained destruction of the federal safety net only will make life more of a misery for everyone, including the deluded MAGA base that elected him in the first place.

|

| Trump once boasted to his MAGA minions that he was their 'vengeance' and 'retribution.' I doubt this is what they expected. |

And leave us not forget the Gestapo-like roundup of immigrants and dissenters, the unconstitutional attacks on free speech and the press—or the worm-brained head of HHS whose idea of a sound policy to fight measles (one of the most contagious diseases ever) is to take huge doses of Vitamin A—and who thinks we’re better off fighting bird flu by letting it run rampant.

And I haven’t even mentioned Greenland or the Panama Canal.

Never in our history has a president reigned over such a cavalcade of idiots and incompetents—with the “very stable genius” himself being the Idiot-in-Chief.

It’s almost as if Donald Trump actually wanted to destroy our country and its democracy.

But that can’t be right—can it?

I am NOT trying to be snide, facetious or clever when I say that it now is apparent that Donald Trump is a Russian asset.

Not, mind you, a Russian agent—that’s a bridge too far even for me, though the internet chatter promoting this idea is getting louder. No, Donald Trump is merely a fat, fatuous, gullible fool: a real estate developer from the outer boroughs who always dreamed of Manhattan; who lied, cheated and bankrupted his way into a series of leveraged deals that made him rich—but never smart, clever, empathetic, or, dare I say it, human.

He was invited to Moscow many years ago, where he was fawned over with promises of investment opportunities. He was made to feel like the winner he never was.

Who really knows what else was said, offered, proffered--or threatened--back then? Or what promissory note, real or symbolic, now has been presented for payment?

|

|

| The day after Trump announced his latest Draconian tariffs, the markets nosedived (yet again) and China responded in kind. The impact on average Americans--and people abroad--will be terrible, most thinking economists agree. |

What IS obvious today is that, with memories of those times still floating in what passes for Trump’s brain, Russian president Vladimir Putin is playing Trump like a violin. One has merely to look at the prolonged dance Putin is engaged in over “peace” negotiations for the Ukraine he invaded to see a former KGB master manipulator toying with, at best, an obese mouse.

The damage to our country that Trump has done in just three months is palpable—and getting worse—which, God willing, may be what ultimately saves us.

While the foreign threat--not just from Putin’s Russia, but from Xi’s China and Kim Jong Un’s North Korea--is profound, the closer-to-home economic and social vengeance that Trump is wreaking is far more on the minds of voters. [BUT…worth remembering here is that, based on post-election polls, it was Donald Trump—not 2024 Democratic candidate Kamala Harris—who was the person most voters believed would better handle the economy and also who best reflected their views of such hot button issues as liberal (read Democratic) elites versus the rest of the country, immigration--as well as letting trans women play women’s sports.]

In other words: it’s not that Democrats lost the ’24 election because they did not turn out enough of their voters. Rather, over the years many of their once-natural constituencies—minorities, immigrants, the working class--had grown fed-up with being ignored or lectured to and decided to give the Orange Pustule a try.

|

| A large part of the blame for electing a traitorous demagogue belongs to Democrats who for too long failed to heed the legitimate gripes of lower and middle class Americans--not to mention immigrants who played by the rules and came here legally. |

So don’t look to the Democrats for help in the run-up to the all-important off-year elections in 2026 that will determine whether they can re-take the House of Representatives and thereby regain at least some political say in how the country is governed following what only can be described as an anti-democracy putsch.

This from the NY Times recently…

“Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) of California said on Friday that the Democratic brand was ‘toxic’ and that his party had to admit its own mistakes, delivering tough love as Democrats struggle in their fight against the Trump administration….He criticized Democrats for being judgmental, staying in an echo chamber and resorting to ‘cancel culture’ to ostracize people whose views they find abhorrent. ‘We talk down to people,’ he said. ‘We talk past people.’”

Also in The Times, columnist Tom Edsall quoted Doug Sosnik, White House political director and a senior adviser for policy and strategy during the Clinton administration, as saying that the upcoming elections—off-year ’26 and presidential 2028—are the GOP’s to lose.

“Bottom line is that we have lost control of our destiny and can only rebound if the Republicans screw up, which is likely,” Sosnik said (echoing in part his former political colleague, strategist James Carville.)

“Having said that,” Sosnik went on, “there is no guarantee that we will benefit unless the voters regain trust that we can govern. It will be up to our 2028 nominee to do that.”

Until then, awful though it is to say, things will have to get worse before they get better.

---------

Frank Van Riper is a Washington, DC-based documentary photographer, journalist, author and lecturer. During 20 years with the New York Daily News, he served as White House correspondent, national political correspondent and Washington Bureau news editor. Afterwards he served 19 years as the Washington Post’s photography columnist. He was a 1979 Nieman Fellow at Harvard and jointly holds (with the late Lars-Erik Nelson) the 1980 Merriman Smith Memorial Award from the White house Correspondents Association.

Van Riper Named to Communications Hall of Fame

|

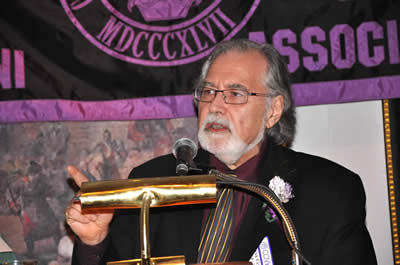

| Frank Van Riper addresses CCNY Communications Alumni at National Arts Club in Manhattan after induction into Communications Alumni Hall of Fame, May 2011. (c) Judith Goodman |

[Copyright Frank Van Riper. All Rights Reserved. Published 4/5/25]

|