Go Back to current Column

NEW: Frank Van Riper classes for Fall/Winter...see below

‘Photo Vero’ – A Modest Proposal

A suggestion to keep all of us honest

By Frank Van Riper

Photography Columnist

It says something that, for at least six years now, Gianni Berengo Gardin, one of Italy’s—and the world’s—finest photojournalists and documentary photographers, has found it necessary to stamp these words on the back of his images, along with his copyright notice:

“Vera Fotografia—non corretta, modificata o inventata al computer.”

[“True photography: not corrected, modified or created by computer.”]

Ah, for the days when we all thought that the camera never lied. Credit digital with calling into question almost everything we hold dear about the camera’s ability to document the world around us accurately and dispassionately.

|

| It has come to this: even a photographic giant like Gianni Berengo Gardin feels he must inoculate himself against any hint that he has digitally manipulated his documentary photographs. (from the book Gianni Berengo Gardin, Contrasto, $65) |

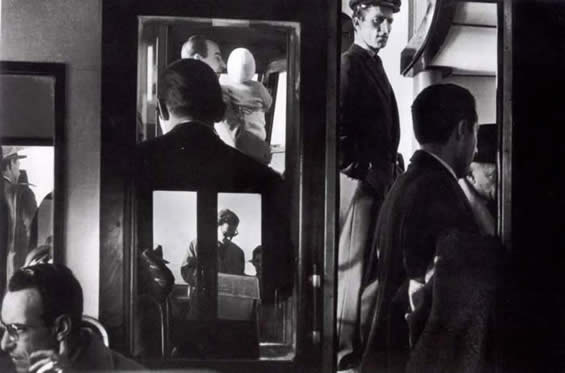

I first saw Berengo Gardin’s notice about computer manipulation (or lack thereof) years ago in the front of his small, brick-thick paperback book, Gli Italiani, and recall thinking at the time that surely such a statement was unnecessary for a photographer of his stature. For the record, Gianni Berengo Gardin has been making brilliant images for more than a half century and is widely regarded as one of the world’s best documentary shooters, easily on a par with the more well known Henri Cartier-Bresson. Like the late, legendary HC-B (who stopped photographing seriously decades before his death on 2004), Berengo Gardin (who is still shooting) is known for his gritty black and white images. And like those of Cartier-Bresson, Berengo Gardin’s photos often are made by available light with tiny Leicas, often are published absolute full-frame, and routinely capture what Cartier-Bresson famously called “the decisive moment” when all elements of composition, gesture and light combine to make a perfect, or near-perfect, photograph.

|

| A simply wonderful photograph by Berengo Gardin that defines The Decisive Moment as well as, or better than, any picture by Cartier-Bresson. Made on a Venetian water bus decades ago, the photo juxtaposes myriad figures beautifully—even creating a bit of surrealism in the figure reflected in the glass. Created in a fraction of a second the image is brilliant; created in Photoshop it would merely be a parlor trick. © Gianni Berengo Gardin |

But then it hit me: if a giant like Berengo Gardin feels it necessary today to distance himself and his work from the morass that can be digital manipulation, surely those of us of lesser reputation and renown run an even greater risk of having our work downgraded, denigrated—even doubted—in the Brave New World of digital.

And this danger extends far beyond the work of individual photographers. I fear that all of photojournalism is at risk of having its work cast aside as mere illustration—a passable representation of an event, perhaps, but--like the engraved drawings of battlefield artists in the years before halftone printing made possible the mass publication of actual photographs--not necessarily a “true” depiction of what is real or of what actually happened.

Far-fetched? I wish it were. But think back just to the recent past and recall when news publications and news agencies were burned by fabricated images. Wire service photos of bombings in Baghdad in which the smoke from one explosion was Photoshop’d into two or three to enhance its dramatic impact. Two good war shots combined into one great one—before the photographer’s “handiwork” was discovered, costing him his job [Brian Walski, ex-LA Times].

Or on a more mundane, but no less egregious, level for its dishonesty: Allan Detrich, former shooter for the Toledo Blade, routinely adding or subtracting elements to his news photos over the course of at least one year, including one dramatic shot of a female basketball player jumping for a ball that Detrich conveniently had inserted into the frame from God knows where. (Happily, this photo was not printed. It was discovered this year, however--complete with bogus basketball--among those he had submitted to his editors for publication.)

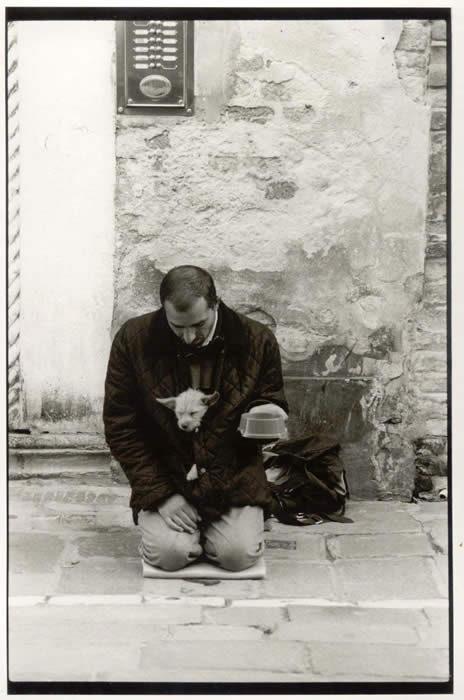

In Venice my wife and partner Judith Goodman made this wonderfully poignant image of a beggar and his dog, capturing them just as their expressions were identical. Could the dog's head have been added later in Photoshop? Sure, but the fact that it wasn't adds to the value of this photo as journalism and as a work of art. (c) Judith Goodman

Surely, these are isolated incidents and the vast majority of professional news photographers would never resort to such visual dishonesty. Or at least I hope not. But in light of the Brian Walski case I also must pay reluctant attention to what some have called “the cockroach theory of journalism.”

You can picture it: turn on the kitchen light at night and, if you see one cockroach, you can bet there are dozens—maybe even hundreds—more nearby, but unseen.

In a case like Brian Walski’s, so this theory goes, when the public sees one news photographer manipulating images as he did, the assumption inevitably will be that this dishonest shooter simply is one of many. And that, in turn, blackens the reputation of everyone in the news business.

In discussing the Walski episode, Pete Souza, former president of the White House News Photographers Association (of which I am a member) made no attempt to defend Walski’s action; he merely expanded its context, and in so doing made an important point about another situation that subtly, though significantly, impacts photojournalism today.

Souza noted that in the case of newspapers especially—but also among news magazines and news agencies—economic pressures are forcing news outlets to rely ever more heavily on un-vetted freelancers, or “stringers,” for images, especially in war zones or other places where it would be too dangerous or, more likely, too expensive to station a regular photo correspondent. Taking nothing away from most stringers’ honesty or courage, the simple fact is that there is nothing like the bond that exists between a staffer and his or her picture desk (stormy though that relationship may be at times) and the unstated though universally accepted belief that news photos must never be manipulated to alter their essential truth.

That is one reason that my wife and I, following the lead of Gianni Berengo Gardin, plan to add this notice at the front of our own forthcoming book of documentary photography, on Venice in winter:

“None of the photographs in this book was manipulated digitally to add or remove compositional elements or to alter the truth of the image.”

To be sure, virtually all major news organizations today expressly forbid computer enhancement or manipulation of news photos, beyond the kind of tweaking and cropping that previously had been done in the darkroom. This latter kind of alteration most often was done to remove extraneous elements from the edges of a news shot or to improve the brightness and/or contrast of an image for reproduction.

But given the sad state of photojournalism today—and the ease with which images can be Photoshop’d into things they are not—it now may be necessary for news outlets to specifically label their news photos as real.

Suppose, for example, the term “photo vero”, or even just “PV” once the term became widely known, were used in each news photo’s caption or credit line to certify that the attendant image has not been digitally manipulated beyond darkroom-like changes to enhance reproduction.

In other words, what you are seeing, dear reader, is a “true photograph,” not a photographic illustration in which an errant telephone wire has been airbrushed out, or an extraneous person or thing has been Photoshop’d from the background, or something has been added (for your benefit, of course) to better tell the story. [Note: such stiff-necked rules would not apply to deliberately done photo-illustrations that accompany news or feature stories. I should note, though, that even today it is common for news organizations to so label these composite images, lest they be confused with the real thing. My suggestion merely takes this one step further.]

Granted, incorporating “Photo Vero” into every caption is like asking every journalist to affirm that he or she is honest and true. (Who, after all, would say otherwise—at least in print?) But my hope is that the practice might up the pressure on those who think that just a little photo manipulation can’t really hurt—and who’s gonna miss that telephone pole anyway?

Finally, there is the simple fact that those of us who love being photographers by definition love the act of “writing with light” (what “photography” literally means). We do not necessarily love “writing with pixels” or “writing with Photoshop” or “writing with whatever new electronic toy comes down the pike.”

More power to those who find their artistic and creative selves in manufacturing wonderful images on the computer. These folks are brilliant photo-illustrators, or photo-manipulators, but they sure as hell aren’t photojournalists or documentarians.

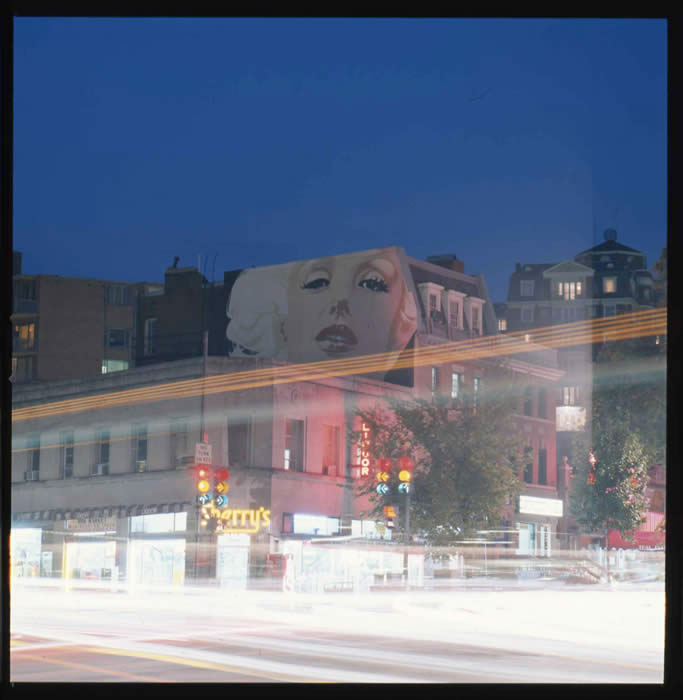

I love, for example, that I was able to create two of my favorite color images of a famous mural in Washington, DC—John Bailey’s giant iconic image of Marilyn Monroe--totally in-camera, with no post-production work at all. It took a lot of planning (thinking how to make the light trails of cars and buses work for me in both images), at least one site visit, and a lot of sitting on a ladder with my tripod-mounted Hasselblad waiting for my version of two decisive moments to occur as day turned into night.

But the end result was worth it, and I didn’t have to go blind in front of a computer screen--amid layers, cutouts and unsharp masks--when the job was done.

Artist John Bailey’s iconic mural of Marilyn Monroe graces the intersection of Connecticut Avenue and Calvert St. in Washington, DC. I wanted to interpret the scene at dusk and at night and show the activity of the bustling intersection. Each exposure was more than a minute—as evidenced by the fact that all the traffic signals are aglow at once. © Frank Van Riper

|

|

Frank Van Riper is Washington-based commercial and documentary photographer, journalist and author. He served for 20 years in the New York Daily News Washington Bureau as White House correspondent, national political correspondent and Washington bureau news editor, and was a 1979 Nieman Fellow at Harvard. Among others, he is the author of the biography Glenn: The Astronaut Who Would Be President, as well as the photography books Faces of the Eastern Shore and Down East Maine/A World Apart. His book Talking Photography is a collection of his Washington Post and other photography writing over the past decade. He can be reached through his website www.GVRphoto.com

Study with Frank Van Riper at Glen Echo PhotoWorks, 2007-08

Master Class with Dr. Flash ($325)

Five-week hands-on studio class (an outgrowth of Frank's popular one-day flash workshop) helps you master small flash units and studio strobes in step-by-step demonstrations. Early registration suggested. (Thursdays, September 27-October 25, 7-10:30pm)

Flash Photography Demystified ($95)

Stop being intimidated by your flash. Frank's intense, user-friendly one-morning hands-on seminar will help you beat your flash unit into compliant submission. (Sunday, October 14, 9:30am-12:30pm) Also: Sunday, February 3, 2008, same time

Documentary Photography: Digital or Film ($300)

Taught by an acclaimed documentary photographer and author. Will help students document their world, more easily photograph people, and work in unfamiliar surroundings. Film or digital welcome. (6 weeks, Thursdays, November 1-December 13 (no class Nov. 22) 7-10:30pm) ALSO: Thursdays, February 7-March 13, 2008, same time

Field Trip: National Gallery of Art, East Wing ($150)

3-meeting National Gallery of art, East Wing, workshop. A brief organization meeting a week before the trip, with the follow-up critique a potluck dinner at Frank's home. Beginning when the doors open at the NGA you will find endless opportunities for shooting--people, architecture, abstracts--all in beautiful light. (Field Trip, Sunday, November 4. Contact instructor for additional dates: gvr@gvrphoto.com or 202.362.8103.

Online registration:

www.glenechopark.org (“Classes & Workshops,” then “Fall, Winter 2008”)

[Copyright Frank Van Riper. All Rights Reserved.]

|