Go Back to current column

2012 Umbria Photo Workshops

Now Spring as well as Fall !! (see below)

Classic Black and White

Why Lisa Tyson Ennis' Wet Darkroom Matters

By Frank Van Riper

Photography Columnist

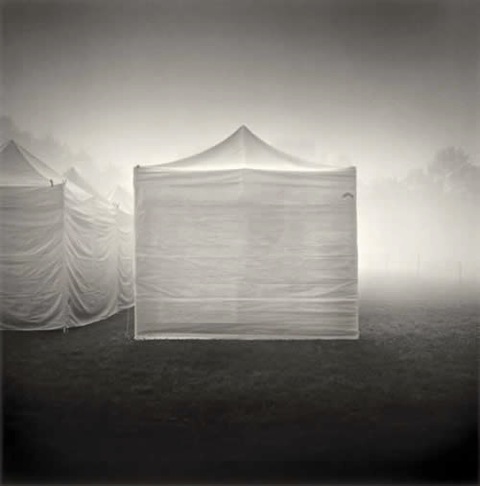

It was around two o’clock in the morning when Lisa Tyson Ennis, in her car after “hanging out with some of my friends,” saw the glowing tent.

“It was a tent at an art fair” in Chadd’s Ford, Pa., she recalled recently--a white structure with straight sides that on any other night would not have caught anyone’s eye. But on this night, at this time, “there actually was moonlight and fog, which is rare. “

There was no choice. Despite the hour Ennis said to herself: “go get your camera.”

Moonlit Tent - (c) Lisa Tyson Ennis. This is not a product of PhotoShop; it happened in the real world, captured by a real photographer working with film.

So it has been with this vivacious, 50-year-old photographer almost since high school, when she first started making pictures. Though she has dabbled in portraiture and other forms of photography, Lisa Tyson Ennis is above all drawn to the landscape and how the natural world arranges itself into its elemental shapes to reflect elegant compositions and produce lasting images.

She works in medium and large format on black and white film. Her exposures can last as long as half an hour. And afterward she makes her own prints one by one in a traditional wet darkroom. She says she never will change.

And because of that the beautiful artisanal work of Lisa Tyson Ennis matters now more than ever.

She is not, strictly speaking, a documentarian—simply recording what happens before her lens, then translating that onto photographic paper.

“Almost all of my work is done in really low light so I am never shooting in full sun ever,” Ennis declared. “[It’s] usually first thing in the morning, like 4 o’clock in the morning, or after the sun is down for a while.” And her exposures, routinely several seconds long, especially in large format, also can last as long as thirty minute, rendering water as smooth as glass, and night skies dotted with star trails.

Star Trails and Animal Sounds - (c) Lisa Tyson Ennis. See how the long exposure turns the water into glass--or clouds--and how the trails of moving stars are faintly visible in the night sky.

“I suppose I am creating a landscape. Since I cannot see what the film is capturing over time with the long exposures, it's always a joy to see in the processed film just what nature was doing (as the waves crash in and recede, or clouds zoom overhead, or leaves rustle in the wind). My soul was also doing some collecting while I waited for that long exposure and all of those feelings as I listened to the waves, birds, seals, wind etc., create a beautiful memory which I try to express in the print once I get back to the darkroom.”

She interprets rather than documents, offering the viewer what might be called her emotional response to a scene, not its passport photo.

“Yes, all the stuff is there,” Ennis noted, quickly removing herself from legions of PhotoShop shooters who live to “improve” their images after the fact by digitally changing, adding or removing elements and thereby shattering what the great Italian photojournalist Gianni Berengo Gardin calls the essential “truth” of a photographic image. She does use all the tools of the traditional wet darkroom—cropping, dodging, burning in, bleaching and toning--“so your eye is more directed to what I want you to look at….(but) no, I don’t move anything around.”

What you see is what you get. But what you get in a Lisa Tyson Ennis photograph also is what she wants you to see.

For the record, Ennis, who was born in Bryn Mawr, Pa., lives with her husband most of the year in West Chester, Pa., near Philadelphia. She summers on Campobello Island, New Brunswick, near Maine. [Currently, they are living on a rented farm in Lubec, Maine—the easternmost point in the US—in hopes of one day settling permanently Down East.]

“I pretty much shoot in the summer and print in the winter,” Ennis noted. Her darkroom in West Chester is “not very big although I have a wonderful 17-foot sink that my husband built for me but even occasionally it is too small because I like to do the printing and then set up the toning trays and just go straight through. But I cant. Sometimes (the trays) are on the floor.”

“I have a Zone 6 enlarger…it’s very fussy but when it’s working it’s beautiful. I also have a Besseler that I use when the Zone 6 isn’t working beautifully.”

Where once she printed on fiber-based graded papers, now she uses fiber-based Ilford Multigrade “exclusively.”

In landscape photography especially, we always return to the Gospel of St. Ansel.

Ansel Adams (1902-84), arguably America’s greatest landscape photographer, and one of the finest black and white darkroom printers of his generation, drew on his training as a musician to coin this perfect simile:

“The negative is the score; the print is the performance.”

In that simple construction, touching on the myriad ways a single image (in this case a black and white negative) can be interpreted in the darkroom (in this case a traditional wet darkroom producing black and white prints) Adams made a slam-dunk case for photography as fine art.

Photographer Lisa Tyson Ennis discusses her gorgeous work, on display at the Lubec Landmarks Gallery in Lubec, Maine. (c) Frank Van Riper

It’s not enough for a photographer to capture a beautiful or striking or historic image in the camera, the bearded, piano-playing, Scotch-loving guru of Carmel, California seemed to say. The real indication of one’s worth as a fine artist, Adams implied, is if you also can translate that image into a superb darkroom-made print.

And not just one print. The amazing thing about photography, especially black and white fine art photography with its infinite variations of white-to-grey-to-black, is that there rarely is one perfect interpretation of an image. Just as different musicians can interpret the same score differently, so too can different photographers (or even the same photographer over time) print the same image differently, sometimes over decades. Adams himself did this years ago for a show at the National Museum of American Art late in his life. It was a kind of Ansel‘s Greatest Hits retrospective that I reviewed for the Washington Post. On a hunch, and to compare Adams’ earlier and later prints of the same iconic images, I brought to the press preview my signed coffee-table edition of his classic book Yosemite and the Range of Light, published by the New York Graphic Society in 1979.

Sure enough, there were marked differences in the tonal range of such familiar images as “Clearing Winter Storm” and “Winter Sunrise, Sierra Nevada.” On balance, the newer prints were starker, more contrasty—punchier, if you will.

Not necessarily better, just different. One still could get lost in the almost platinum-print midtones of his earlier interpretations, arguably reflecting both the artistic tastes of the time as well as the actual range of his printing media and chemistry.

It simply brought home to me—again—how much of the artistic process occurs in the darkroom, after a photograph has been taken.

To be sure, Adams—who was both master photographer and master printer—viewed the physical process of photographic printing as a wholly separate art form. Easy for him, one could argue, since he was great at both. And also, to be sure, some of his great contemporaries: photojournalists like Henri Carter-Bresson and Robert Capa, almost never worked in the darkroom, being too busy traveling the world documenting society or covering breaking news to spend any significant time getting their hands wet.

No, it often falls to the landscape photographer to carry this double burden, the best among them seeming to carry it effortlesly: folks like John Sexton (who once worked with Adams), Michael Kenna, Joel Meyerowitz, Robert Adams, Stephen Shore, et al.

Part of the reason for this is that landscape shooters by definition must work slowly, painstakingly, to set up their shot. In many cases a landscape photographer might spend hours setting up for a photograph—don’t forget waiting for the right light—and then make only one or two exposures. Having expended such effort to record an image on film, does it not stand to reason that this artist also might want to make sure that the resultant image is the best it can be? And in many cases--though not necessarily all--that means making the print oneself, by hand, especially if the image is black and white.

Much has been made (correctly) of digital’s ability to make gorgeous prints, And, in fact, color shooters like Meyerowitz now rave about the ability of their digital printers to make wonderful—and huge—prints that would have been near-impossible to make as well by hand in a wet color darkroom. And I have to admit: huge 3’x4’ black and white exhibition images from our book Serenissima: Venice in Winter are in fact black and white digital prints on watercolor paper—albeit made from scanned 11x14 silver prints that I made by hand in the darkroom. I still insist, though, that something is lost when the final step in the process of producing fine photographic prints is letting a robot churn them out unthinkingly by the dozens with the push of a button.

In talking to Lisa Tyson Ennis, the novice might remark on how much she does before she even presses the cable release on her Hasselblad or her view camera, much less how much time she spends later laboring in the darkroom over each gelatin silver print.

This past summer, during an exhibition of her work in Lubec Maine, where my wife Judy and I teach photography workshops (www.SummerKeys.com --Lubec PhotoWorkshops) Lisa graciously lugged a big rolling equipment bag to the gallery to show our workshop students some of what she brings to a shoot.

“I do use a lot of neutral density filters (as well as) red and orange. Sometimes I stack filters,” she said, unlimbering a wonderfully hefty and retro Hasselblad 503C medium format film camera. [Note: stacking filters can lead to vignetting at the corners of the frame, but often that is an effect that Lisa seeks.]

Her tripod is a big thing—big enough to hold steady a 4x5 view camera (she recently acquired an 8x10.) Looking at the tripod one is reminded of the old truism: there are small tripods and there are sturdy tripods, but there are no small sturdy tripods.

Lisa at work. Note the muscular tripod and bag full of equipment. Obviously, these are not casually-made happy-snaps. (Courtesy Lisa Tyson Ennis)

“In this show, exposures were not that long; maybe six seconds or something…(but) this one over here is actually nighttime…about a half an hour, showing star trails.”

“This is on Grand Manan (a large island off the Maine coast)…a great spot to look down on the weir.” A weir is a very old tool for catching fish—thought to have been invented by native peoples—that basically is huge net suspended in the water by a series of rough-hewn wooden poles. “They’re all shaped differently,” Lisa declared, “it’s really magical. “ And certainly, this image looks magical—almost as if the weir were floating in the clouds.

One of several weir studies that Lisa has made, making use of long exposures to give an etheral cast to this ancient fishing tool. (c) Lisa Tyson Ennis

In fact, the cloud-like effect is the result of a combination of a long exposure rendering the water glassy-smooth and the overhead clouds being reflected in that surface.

But how does one meter for such a photo?

“You just have to guess,” Lisa said. Sophisticated spot meters can offer some parameters for gauging f-stop and shutter speed, but when you work in the wild blue yonder of minutes-long exposures experience becomes the best teacher.

Couldn’t you bracket exposures, one of our students asked.

“It depends on how much light there is,” Lisa replied. “For example, if it’s gonna be, like, a 30-minute exposure, you’re not going to do much bracketing.”

Such ability to gauge correct exposure through experience also explains Ennis’ move to Fuji Acros BxW film from her previous favorite, Kodak T-Max 100. Very long exposures can produce an effect called reciprocity failure. In color film, this can mean bizarre color shifts, even if the “exposure value” for the long exposure is identical to that of a shorter one. In Lisa’s case, working in black and white, she said she found the T-Max film routinely underexposed during long exposures while the Fuji film did not. So she switched.

As digital technology inevitably improves, both in image capture and image printing, it is reasonable to ask whether people like Lisa Tyson Ennis are dinosaurs. As a longtime black and white film photographer and printer myself I concede that the argument that film captures more detail than digital is now all but moot. And there is no doubt that digital printing, in both black and white and color, can be glorious.

I also have to admit that, as commercial photographers, my wife Judy and I probably can’t remember the last time we shot film: literally all of our commercial work today is digital, be it for annual reports, corporate or association websites or even for the occasional wedding or bar mitzvah that we still do, mostly for former clients. And, of course, our workshops, in both Maine and Italy (www.experienceumbria.com) are all digital, the better to review students’ work in real time.

That having been said, I firmly believe that in the world of fine art photography there always will be a place—and a market—for the individually made black and white wet darkroom print. In a world of mass production and cheap plastic, a stunning signed print, that has been individually made by the artist in a darkroom whose components have barely changed over nearly two centuries should have the same appeal in the marketplace as any other handmade artisanal object or one-of-a-kind work of art.

It will ever be thus and all comes back to St. Ansel’s dictum that the negative is the score; the print the performance.

“I believe in the handmade print,” Lisa Tyson Ennis declared. “Each print is its own piece. I also love the soft cave-like quality of the darkroom, where I can shut myself in for hours at a time and really focus on the prints.”

Focus on the performance.

In the case of work by photographers like Ennis, that performance is by a living human being, not a machine. And each print is unique, each print individual, each print made by hand.

ANNOUNCING…

The Umbria Photo Workshops

Now every Spring..as well as Fall!

Spring 2012 dates….May 5-12

Fall 2012 dates…October 13-20

Judith Goodman Frank Van Riper

Join internationally acclaimed husband and wife photographers Frank Van Riper and Judith Goodman for weeklong photographic workshops under glorious Spring and Fall skies in one of Italy’s most beautiful regions. Note: Workshops are limited to only six participants and include lodging at the spacious and inviting Villa Fattoria del Gelso in Cannara.

Frank and Judy, authors of the award-winning book Serenissima: Venice in Winter, will share their image-making techniques with a small group during a simpatico, low-key week covering everything from landscape photography in the verdant hills of Umbria, to nighttime photography using available and artificial light, to location portraiture in Umbria’s closely held olive fields and vineyards.

Small class size assures individual critique and instruction.

Fee includes villa accommodations, all breakfasts, daily wine and antipasto Happy Hour, welcome and farewell dinner, pizza night, transportation by private van.

No entrance requirements beyond a love of good food, fine wine and photography.

Sign up now for a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

-------

Price per person: €1800 (convert to dollars)

Single supplement 400 Euro

Limited to 6 participants

Package includes:

--7 nights in the private villa Fattoria del Gelso

--welcome and farewell dinner

--all breakfasts

--vineyard tour and private lunch

--pizza-making party at the villa

--daily wine and antipasto happy hour

--individual critique and instruction

--private guided walking tours

--ground transportation throughout your stay

—FURTHER INFORMATION: www.experienceumbria.com

Van Riper Named to Communications Hall of Fame

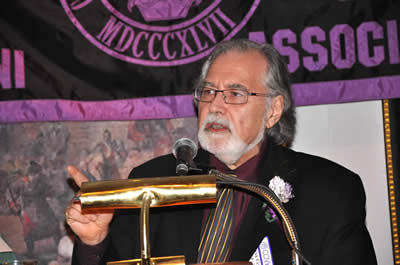

Frank Van Riper addresses CCNY Communications Alumni at National Arts Club in Manhattan after induction into Communications Alumni Hall of Fame, May 2011. (c) Judith Goodman

Photography columnist Frank Van Riper, author of the award-winning bookDown East Maine/ A World Apart, and others was inducted into the City College of New York Communications Alumni Hall of Fame during an awards dinner at the National Arts Club in Manhattan May 6, 2011.

Van Riper, 64, was cited for is long career in journalism and photography and joins a panoply of other famed CCNY writers and artists named to the Hall of Fame in previous years, including playwright Paddy Chayefsky, muckraking author Upton Sinclair, novelist Oscar Hijuelos and columnist and author Irving Kristol.

Van Riper’s formal journalism career began on the New York Daily News, which he joined in 1967, one week after his college graduation. He stayed with The News for 20 years, serving as White House correspondent, national political correspondent and Washington Bureau news editor. He was a 1979 Nieman Fellow at Harvard, and holds the 1980 Merriman Smith Award (with the late Lars-Erik Nelson) from the White House Correspondents Association for deadline coverage of the negotiations to free American hostages held in Iran during the Carter administration.

In 1987 he left daily journalism for commercial and documentary photography, partnering with his wife, photographer and sculptor Judith Goodman.

In 1992, Van Riper became photography columnist of the Washington Post, where his column, “Talking Photography,” appeared in the Camera Works section of Washingtonpost.com (www.TalkingPhotography.com) His book, Talking Photography, a ten-year collection of his columns and other photography writing, was published in 2001.

Van Riper and his wife are co-authors of Serenissima: Venice in Winter, an internationally acclaimed book of photographs and essays, published in 2008.

In October, 2010, they also inaugurated The Umbria Photo Workshops, their first international photography workshop in Umbria, Italy. www.experienceumbria.com

Every summer they also lead the Lubec Photo Workshops at SummerKeys, a series of low-key week-long workshops based in Lubec, Maine. www.SummerKeys.com

Faces of the Eastern Shore

Order Frank Van Riper’s classic look at life on the Chesapeake, Faces of the Eastern Shore, for only $15 (reg. $19.95), plus s/h.

Published in 1992 and printed in duotone, this 10”x 9” quality paperback was featured in the Baltimore Sun, Washington Post and numerous other publications for its superb location portraiture and lyrical text.

Said author James A. Michener in his foreword: “What this rascal has done is belatedly to illustrate my novel, Chesapeake, and superbly.”

ContactGVR@GVRphoto.com

[Copyright Frank Van Riper. All Rights Reserved. Published 10/11

|